We English speakers are used to having our language understood in many parts of the world, where local citizens have learned it because of its ubiquity on radio and TV. But what happens when a language goes the other direction? In the Shetland Islands, once occupied by the Vikings, the language called Norn was superseded by the 15th Century, leaving almost no written remains. Similar to Faroese and Icelandic, the language can be heard today only in a few words used in sheep-herding that describe the color and pattern variations in the local sheep. The last Norn speaker probably died out some time in the middle of the 19th Century.

Wander around in the Shetlands today and you’ll still hear a bit of Norn in place-names and words related to the weather and fishing, but that’s about it. Something similar happened to Cornish, the Celtic language descended from the tongue widely spoken in Britain before English. Cornish may have made it into the 20th Century in some families, but the outlook for the language is actually brighter than Norn’s, with a revival of interest that has led to the old tongue being reintroduced in many schools. A man named Henry Jenner kicked off the Cornish revival with a grammar of the language in 1904, and a standard written form has now been introduced.

All of which gets me to the warm and fuzzy feelings I’m having about Google. Used to keeping an eye on giant digital firms because of privacy concerns, I have to hand it to the company for its latest project. The Endangered Languages Project (www.endangeredlanguages.com/) is an ambitious plan to document over 3,000 languages — this is about half the number known to exist — that are considered on the edge of extinction. Languages like Miami-Illinois, spoken by the Miami tribe in the American Midwest, an Indian tongue whose last fluent speakers died in the 1960s. A member of the tribe is now trying to resurrect the language by publishing educational materials for Miami children and collecting audio files to preserve its pronunciation.

Google’s plan is to help people who are doing this kind of work on their own or in small groups by providing tools and resources that include recordings of people speaking the languages, online language courses and copies of historical documents in the language in question. And if you’re thinking this is Google once again sounding out a new advertising venue, guess again. The company plans to hand off the management of the site to the First Peoples’ Cultural Council and the Institute for Language Information and Technology at Eastern Michigan University.

Google is saying that without action, 50 percent of the 7,000 languages currently spoken will not survive into the next century. The site will allow users to make their own contributions, using tools provided by Vizzuality, a data management specialist, to upload materials and add comments. By centralizing the language preservation task, the company opens up opportunities for conversation between linguists both professional and amateur on the best ways to proceed, along with a format that will make it easy to cross-reference the various projects being developed. Research into the threatened languages is also being provided by the Catalogue of Endangered Languages, with funding by the National Science Foundation.

I probably should have seen this coming after Google’s 2011 move to add Cherokee to the language interface for its search engine. The move makes abundant sense, for there are 300,000 people in the Cherokee nation who until last year were unable to use the Internet’s most iconic search engine in their own language. Now they can, with an on-screen Cherokee keyboard provided for those without the physical keyboard containing the characters of the Cherokee alphabet. Spoken largely in Oklahoma and North Carolina today, Cherokee joins Google’s list of 146 interface languages, but it’s clear that the list will continue to grow.

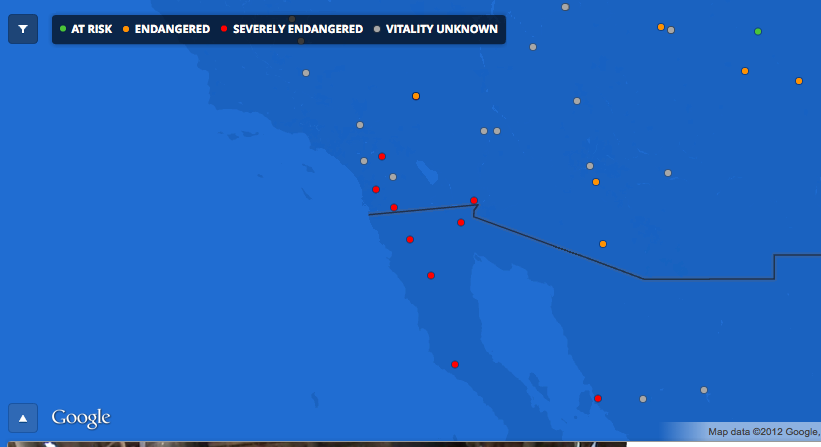

The First Peoples' Heritage, Language & Culture Council, based in British Columbia, has already been active on the endangered language front, developing keyboards that could support 34 languages and 61 dialects present in British Columbia alone, along with online chat tools. Have a look at Google’s Endangered Languages site and you’ll see that this is barely scratching the surface. A global map is littered with the red icons marking severely endangered languages, and it’s astonishing to see how many languages are represented today by fewer than 100 speakers.

It took a Rosetta Stone to help us figure out Egyptian hieroglyphics by comparing the three scripts shown, two of them already understood. That was at the end of the 18th Century, when a French expedition to Egypt turned up the artifact. How will the future translate the remains of languages threatened with extinction today, and how will anyone know what these languages sounded like unless we take pains to record and preserve them? Good for Google’s involvement in a project that preserves the knowledge and tradition of cultures we are rapidly losing.