The latest news from Mars highlights a profound and deeply ironic fact: It is possible that the first life we detect from another planet will not be found here in our own Solar System. That this is striking is clear from the numbers. Mars is 364,000 times closer to us (when at the closest point in its orbit) than Proxima Centauri, the nearest star. Even tiny Enceladus, the Saturnian moon whose frequent geysers tell us of a probable ocean beneath its surface, is 29,000 times closer to our planet than this dim red dwarf, one of the three stars making up Alpha Centauri.

With rovers on the nearby Red Planet and a determined effort to find life there, how can we imagine we’ll find life on unspeakably more distant planets, worlds that we can’t, for the most part, even see? The answer lies in what we can learn about planetary atmospheres, and here the latest from Mars is a bit discouraging. NASA’s Curiosity rover tells us that it has failed to detect any methane in the planet’s atmosphere. Methane can be produced naturally, but it is often a byproduct of living processes, and its discovery would enhance the prospects for life.

In fact, earlier work has implicated Mars as the home of trace amounts of methane, though this work came not from the surface but through a European orbiter and in another case by telescopic observations from Earth. Is there methane there or not, and why is it proving so elusive? The truth is that even with a methane signature, we’ll need more advanced instruments on the surface, and there are those who argue that to make the final case for Martian life, we’ll need astronauts on the surface with the proper equipment to find it. The same may be true of identifying earlier life that may have died out as Mars evolved over geological time.

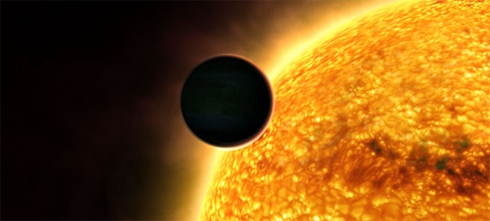

But here’s the striking news: We’re already looking at the atmospheres of planets around other stars. In fact, a planet with the designation HD 189733b has proven remarkably useful in teaching us the craft. Astronomers use instruments called spectroscopes to study this gas giant orbiting in an extremely hot orbit close to its star. Because HD 189733b crosses in front of the parent star as seen from Earth, we can take readings of the starlight without the planet in transit and other readings when the world is in front of or going behind the star. The difference between the two analyses yields information about what’s in the atmosphere of this planet.

Nobody is talking about life on HD 189733b because it’s so close to its star, and thus far what we have detected — water vapor, methane, sodium, carbon dioxide — is of interest because of what it tells us about the planet itself. But the larger game is afoot. A scientist named Sara Seager from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology is now saying that we have an outside chance of finding the signs of life on a smaller world around a much smaller star within the next ten years. We’ll do that by identifying candidate planets through upcoming space missions and then, using the James Webb Space Telescope (to be launched in 2018), we’ll study the starlight playing off their atmospheres to look for the characteristic signs of life.

Hunting for these so-called biosignatures is tricky business, because a star’s light absolutely overwhelms the tiny trace of a planet next to it. In his book "Five Billion Years of Solitude," space writer Lee Billings likens it to “photographing an unlit match adjacent to a detonating hydrogen bomb.” But there are ways to make it easier. Red dwarf stars are considerably smaller and dimmer than the Sun. An Earth-like planet near one of these would be more readily detectable, and even though serious issues remain — such planets would have to be close to their star to be habitable, and that might make them tidally locked, with one side always facing the star — we could subject their atmospheres to a search for gases characteristic of living things.

Oxygen by itself would be an interesting finding, but there are ways to produce oxygen that don’t involve life. More interesting would be the simultaneous presence of oxygen and methane, for their co-existence implies they are being continually replenished in the atmosphere. The question then is, by what? For if oxygen and methane exist in the same place, they should turn into carbon dioxide and water unless life is somehow sustaining the mix. Finding water vapor and carbon dioxide in the same atmosphere along with oxygen and methane would also tell us much about the planet’s habitability and the likelihood of liquid water on the surface.

Get the right combination of gases and the case for life becomes strong. Our ground- and space-based instrumentation is getting sufficiently sensitive to make such detections, and if MIT's Seager is right and we find such a planet within the next 10 years, then we may be announcing probable extraterrestrial life around other stars long before we identify it on Mars or Enceladus.

Whether or not this is the case, the fact is that we are truly in the golden age of exoplanet discovery, with close to 1,000 already confirmed and thousands still waiting to be confirmed, most of these through the Kepler mission, which has been an outstanding success despite the recent gyroscope problems that have now shut down its primary mission. We still have years of data from Kepler to sort through, which will tell us much about the statistical likelihood of Earth-sized planets around other stars. Ahead is the main event, the search for signs that life can begin and thrive on settings other than Earth. We may not have to wait long to find out.