"Whenever people agree with me, I always feel I must be wrong." – Oscar Wilde

You're sitting in yet another meeting. Your colleagues are nodding and otherwise sending signals of agreement. You wonder if you're the only one seeing a problem here.

All caffeinated and ready to jump out of your seat, you calm down. You want to say something, but you hold back. You stifle yourself, rationalizing that the others have more experience, more information, more insight, more intelligence, etc.

As the meeting breaks up, you take up a conversation with one of your colleagues. It turns out she feels the same way you do — ahhh, sweet validation. Could others have been thinking what you were thinking? You weigh the perceived benefits and risks of revisiting the matter, and you opt to move on. After all, you've learned to pick your battles. You give yourself a high five and tackle another project, one you can actually check off the list at the end of the day.

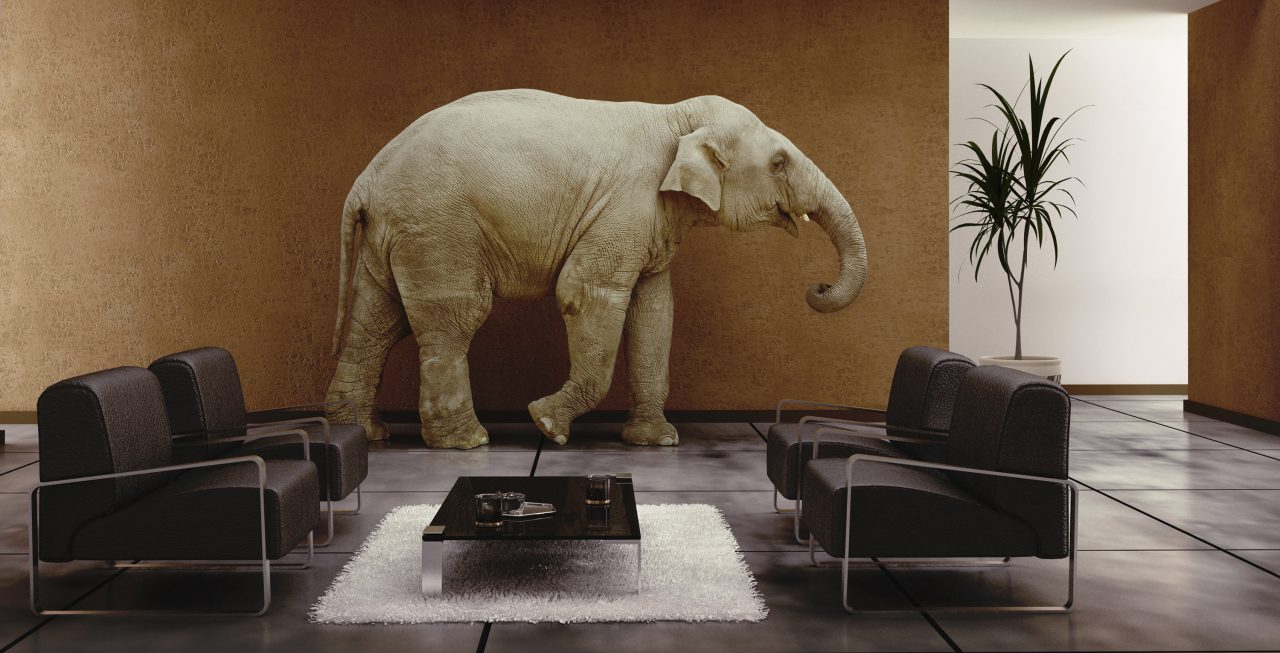

Nearly every day we can pick up the paper and read about elephants. Not the pink kind, but the proverbial elephant in the room. When GM failed to name their elephant — which involved faulty parts in the Chevy Cobalt — it resulted in at least 31 crashes and a dozen deaths. As field reports about these crashes started surfacing in GM's legal department, it became clear their safety engineers were not informed until two years later. Why? A law meant to hold automakers accountable created an unwritten cultural code that evidence about such defects shouldn't be moved up the chain of command until absolutely necessary.

So how does this apply to you and your company?

We've learned that most companies are full of untapped brilliance found in the form of seemingly small comments, observations, concerns or questions. This type of inquisitiveness is meant to test assumptions, and we believe it is extremely important to the health and wealth of the organization to encourage it. When an issue or concern is surfaced in a constructive manner, without placing blame, the matter can be taken into consideration, evaluated and resolved. What follows is innovation, employee engagement and ownership for business results. Risks can be more easily managed.

Naming elephants takes courage, skill and discipline. It is a learned behavior easiest to practice in a culture that encourages disturbing the status quo — a culture that values questions as much as answers. It requires a choice that people make to exercise their personal power. They find their voice, and they name those elephants.

It may feel risky at first, but perhaps not nearly as risky as ignoring the elephants altogether, hoping they will just go away.