There recently arrived in the mail a heavy book package. The arrival of a book is no rare event in this household, but I was nonetheless puzzled, as I usually remember what I have on order.

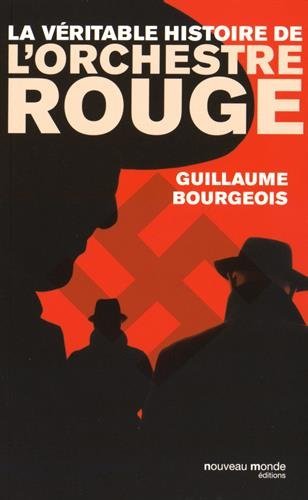

I opened it to discover a thick paperback (nearly 600 pages) entitled "La véritable histoire de l’Orchestre rouge" — "The Real History of the Red Orchestra" — by Guillaume Bourgeois. It was a complimentary copy with a nice author’s inscription. The cover art is catchy: superimposed dark silhouettes of trenchcoated “spooks” upon a swastikaed red background.

As many readers will know, the Red Orchestra was the name given by the Nazi counter-espionage agencies to the Russian spy rings working in western Europe just before and during World War II. In the slang of the German agencies, spies were “violinists.” Hence why the Sonderkommando (special unit), established by the Nazi authorities to root them out, called the large ensemble of Communist spies an orchestra, the Rote Kapelle. In terms of the popular espionology of action movies and spy thrillers, no group is more famous than the Red Orchestra and no single spy more heroic than its conductor, the legendary Leopold Trepper.

As for the book’s author, Guillaume Bourgeois, a professor of modern European history at the University of Poitiers, he is not a complete stranger to my blog. He was my host on a memorable picnic at Vaux-le-Vicomte, which I wrote about at the time last year.

We first met soon after I had published "The Anti-Communist Manifestos" in 2009. One of the four anti-Communist bestsellers I had written about was "Out of the Night" (1941), by a one-time German Comintern agent named Richard Krebs. This man became famous overnight under his pen name, Jan Valtin, with the publication of his blockbuster. For although I had never heard of the book when I stumbled upon it in a junk pile in Cranbury, New Jersey, it was the bestseller of its year and played no insignificant role in the literary history of the Cold War and especially in the creation of American anti-Communism.

Bourgeois, an expert on Communist activities in the pre-war European maritime unions, knew a great deal about Krebs/Valtin. Slightly embarrassingly indeed, he knew more than I did despite the fact that I had published a couple of essays on him based on archival materials in the Princeton library.

The received wisdom concerning the Red Orchestra is that it was one of the most successful espionage groups of all time. Its leader was Leopold Trepper (1904-1982), a Polish Jew whose development, like that of Arthur Koestler, took the not uncommon path through youthful Zionism to Communism. He was recruited by the GRU and eventually was directing several loosely connected espionage groups in Germany and elsewhere in Western Europe, especially Belgium and Switzerland.

Readers of John le Carré and Alan Furst will know something of the weirdness of living in a hall of mirrors presided over by faceless manipulators of disinformation and handlers of double agents. Such authors might prepare them for Trepper’s autobiography, "The Great Game" ("Le grand jeu", 1975). According to Trepper, the “great game” was the complicated ruse by which he was able repeatedly to hoodwink the Abwehr (German counter-espionage) and to deploy a major engine of resistance under the very noses of the German occupiers.

Using mainly amateur but politically committed agents, the Red Orchestra was able to deliver a veritable motherload of crucial information to Moscow. Part of the Trepper legend is that he actually forewarned Stalin of Operation Barbarossa (Hitler’s stab-in-the-back invasion of his treaty ally, the Soviet Union, in June of 1941). Unfortunately Stalin refused to believe him. Likewise the Red Orchestra was credited with stealing and transmitting information crucial to the Soviet victory at the Battle of Stalingrad (autumn and winter of 1942-1943), the turning point of the European war.

That is essentially the history of the Red Orchestra in most books on the subject, and what’s not to like? Surely we all love to imagine detestable Nazis in their spit-and-polish uniforms being outfoxed by grizzled peasants in berets, frumpy housewives and old, nondescript guys in really bad suits — you have seen it a dozen times in the movies. This heroic history was pleasing to the war’s victors and especially to the French Communist Party, which advertised itself as the heart of the Résistance and the “party of the 75,000 fusillés” — the number of their comrades who had faced German firing squads. Later, in the Cold War, ex-Nazis and other Germans had their own reasons to encourage the West to fear the nearly supernatural powers of Soviet intelligence. But is this the true history of the Red Orchestra?

One of the big problems in studying spies is that spies are, quite literally, professional liars. Unfortunately they don’t always start telling the truth when they turn to autobiography. That is the problem I have with Jan Valtin. Not all that many super spies live to tell about it. Those who do can reasonably expect that there are few other survivors in a position to contradict their fibs. Unfortunately for them there are archives. Guillaume Bourgeois has been chasing the history of Communist espionage through the archives of Europe for the last 20 years.

To call his findings “revisionary history” is putting it mildly. This terrific book will surely soon be translated into English for the convenience for the large number of espionage buffs in the English-speaking world. For the moment I shall say no more than that it is comforting to learn that on occasion truth is not stranger than fiction, just more interesting.