There are two Raleighs in North Carolina, the city that is and the one that it is becoming.

One is a smaller city defined by leafy neighborhoods, affordable housing and reliance on cars. The other is a growing metropolis with an urban core ringed by islands of high-density development, all knit together by rapid transit.

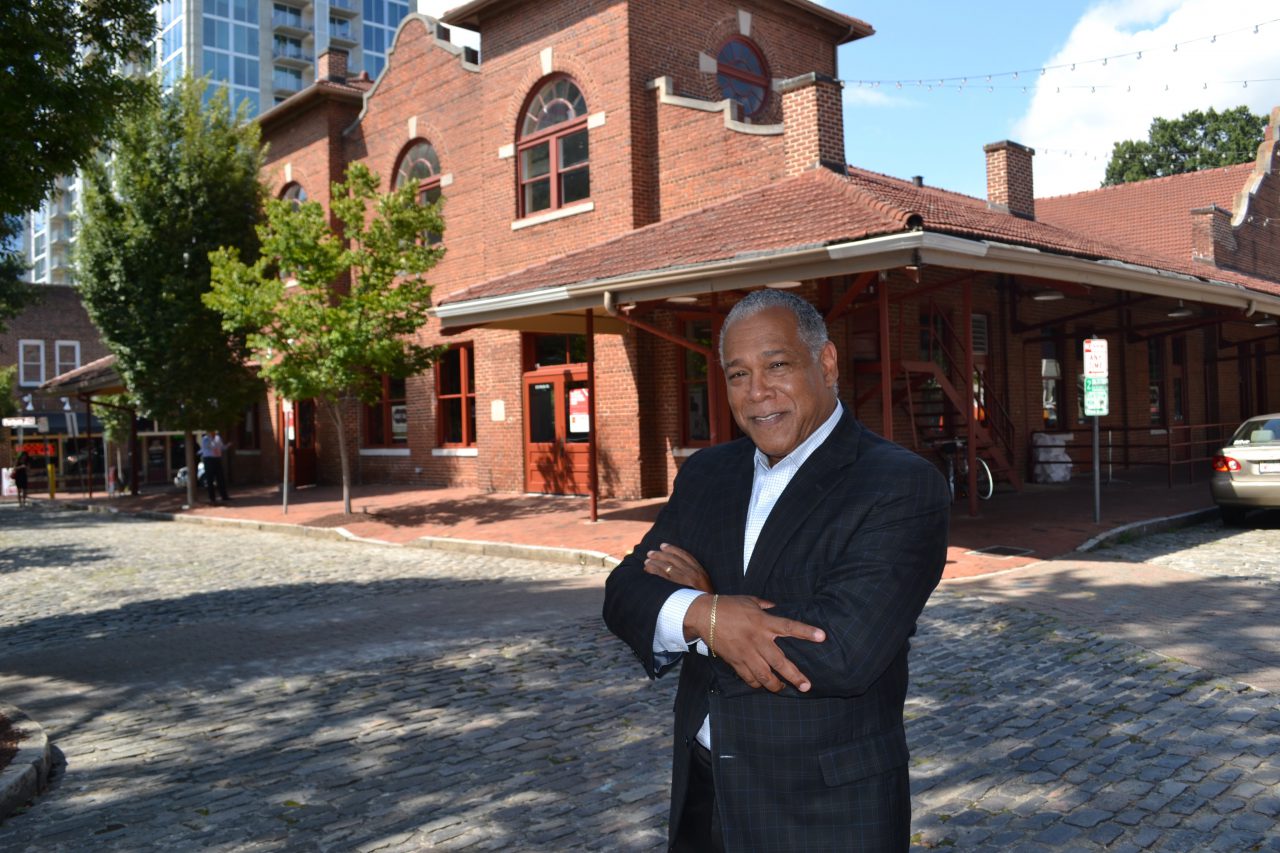

The route from the first Raleigh to the second passes through the mind of Mitchell J. Silver. As Raleigh’s planning director from 2005 to 2014, Silver outlined what one of the nation’s fastest-growing cities could grow into without losing its character and balance.

Or, as the late Raleigh City Councilman Thomas Crowder once put it, the North Carolina capital could become “a first-rate Raleigh, or a second-rate Atlanta.”

That choice was not Raleigh’s alone. It is a choice facing many small and mid-sized cities in the South and West as population growth pushes into warmer and more affordable urban locations. The trick is to develop the amenities and appeal of a larger city while avoiding the ugliness and congestion of sprawl.

The proper handling of growth is not as simple as zoning that steers development, Silver says. A good plan also has to limit the uprooting of current residents as new growth is concentrated and land values rise.

The essential element in balancing the interests of current and arriving residents, Silver says, is dense development.

“If you have a neighborhood with 200 residents and you build 800 units, you have room for everyone to stay,” he says.

Powerful shifts in urban land use and the effects on displaced residents is not merely a professional interest for Silver. He is one of only about 5 percent of urban planners who are African American, and he knows personally the dynamics of urban decay and resurgence. He grew up in Brooklyn and saw its decline in the 1970s and its recent resurgence into a place where, he says, he couldn't afford to buy a home.

Yet Silver, 55, doesn’t regret the changes to his former corner of New York. He welcomes the improvement.

“People use gentrification too liberally,” he says. “It is revitalization and revitalization has tradeoffs. The alternative is to leave the neighborhood in bad condition.”

Silver came to Raleigh after working as a planner in New York City and Washington, D.C. He left in 2014 to become parks commissioner of his native New York City. There, he’s advancing Mayor Bill De Blasio’s goal of greater equity by upgrading scores of neglected parks in low-income areas. But he keeps a close eye on the comprehensive plan he left behind. It will guide Raleigh’s transition into a far more densely populated city.

Raleigh’s population has soared from 276,093 in 2000 to 439,896 today, and its geographic footprint has expanded through annexation. But the city is reaching the limits of expansion, and there is a need to accommodate the continuing growth in population. By 2030, Raleigh’s population is projected to be 71 percent higher than it was 2010 – a rate that ties it with Charlotte as the fastest growing among larger U.S. cities.

The plan Silver and his staff settled on was to sharply increase density in eight “growth centers” connected by roads and transit that would serve as ”growth corridors.” The plan has drawn praise from planners around the nation and its early results have given Silver, a past president of the American Planning Association, deep professional satisfaction.

“It’s something I’m proud of and it has worked,” says Silver, who visited Raleigh in September for a conference on innovation. “Sixty percent of the growth has happened within growth centers exactly as planned.”

Silver is nervous about political pressures limiting the full implementation of the plan. He says residents in some areas will have to accept more apartments and taller buildings to absorb that influx.

“Where you say no to higher density, it’s going to pop up in other places, and you get sprawl,” he says. “It’s not like [growth] is going to stop.”

In Raleigh, Silver needed to design more than a graceful way to grow. He also had to devise a plan that would not displace established residents, especially those in the mostly African-American area of Southeast Raleigh, where the closeness to downtown offices and entertainment made it ripe for new development.

Silver says more density is the way to avoid displacement. Much of Southeast Raleigh is single-family homes. More multi-family housing will create room for new people and room for longtime residents to stay.

Dan Coleman, a land use consultant who heads a citizens group in Southeast Raleigh, says Silver’s solution is being resisted by residents who want to keep their homes or be provided affordable new homes rather than apartments, town homes or condominiums.

Coleman says Silver tried to persuade residents on the value of density without success.

“He just ran up against a brick wall,” Coleman says.

Silver says eventually the resisters will see the wisdom of changing a neighborhood in order to stay in it.

“You have to manage those [growth] trends, and a key issue is displacement,” he says. “You do that through density. Provide an opportunity for people to stay if they want, but make room for people to come in.”

One of those coming will be Mitchell J. Silver. He still has family in Raleigh and plans to retire here.

“I have a very special place in my heart for Raleigh,” he says. “It’s a great place to live.”

With luck, and his plan, it will stay that way.