Clint Eastwood is the reason we have the new film “J. Edgar.”

It’s not like the moviegoing masses were begging for a biopic about longtime FBI director/pathologic paranoiac J. Edgar Hoover. How many of today’s mall rats can even identify him?

The subject matter isn’t “sexy.” His story isn’t familiar to anyone under the age of 50. There are no obvious marketing hooks.

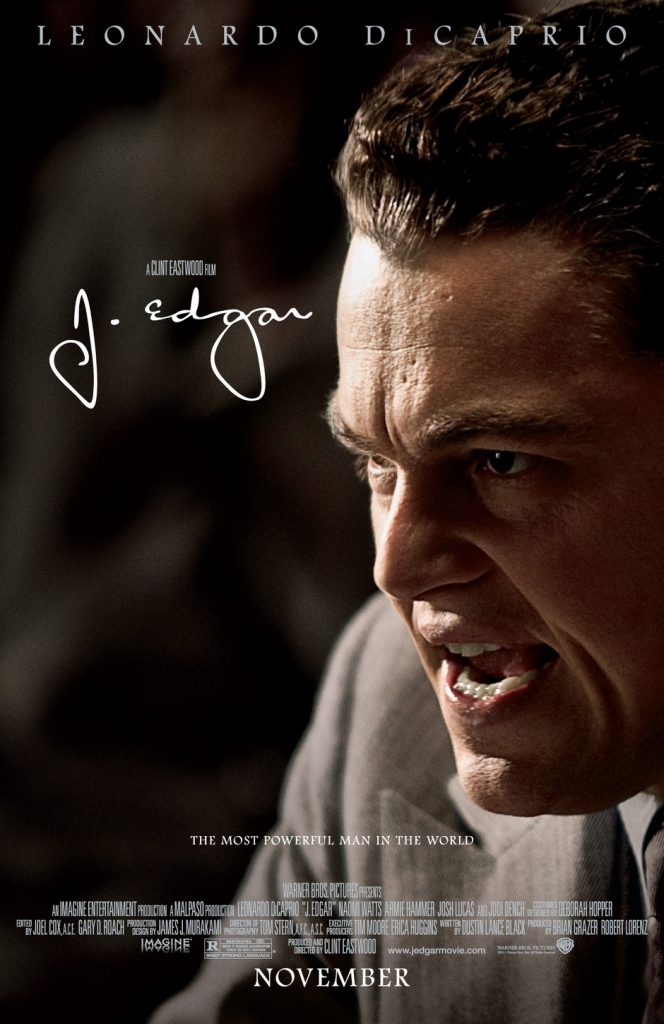

Not even the presence of one-time teen heartthrob Leonardo “Titanic” DiCaprio in the title role (an amazing performance that I, for one, didn’t see coming) can make this production anything but a money pit.

And yet here “J. Edgar” is, all because Clint Eastwood found Hoover’s story fascinating and has the track record, personal loyalties and financial clout to make movies nobody wants to see…or rather movies they think they don’t want to see.

And you know what? “J. Edgar” is a good movie.

Not great. Not flawless (it’s really long and doesn’t give us anyone to root for.)

But a movie that examines a much-reviled figure with a surprising degree of, if not sympathy, then honest insight.

Eastwood’s film is set simultaneously in the present (in this case the late ‘60s) and over the previous 40 years. At the desk at FBI headquarters from which he has ruled for decades, an aging J. Edgar Hoover is dictating his memoirs to a deferential young agent.

We will see that his account is overflowing with self-aggrandizement, justifications, outright lies.

We observe his capricious wielding of the FBI’s power, of his almost religious mania concerning the Communist threat, and the weird logic that allows him to defend the “American way” via methods (spying, blackmail, entrapment) that violate that very way.

But we also witness how Hoover almost singlehandedly ushered in the modern era of crime fighting, championing a scientific approach now universally embraced by law enforcement.

We witness momentous moments — such as the Lindbergh kidnapping and Kansas City Massacre — from the FBI’s annals.

But against this cavalcade of history, Eastwood and his screenwriter, Dustin Lance Black, present a character study about a man who lived his life in near-solitude.

J. Edgar Hoover had no close personal friends. The great loves of his life were his domineering, old-school mother (Judi Dench) and the FBI which was essentially his child.

With only two individuals did he have relationships of more than a merely perfunctory nature. One was with his longtime personal secretary Helen Gandy (Naomi Watts), whose officious stewardship of Hoover’s “secret files” allowed him to thwart every attempt by several presidents to replace him. (His files documented JFK’s and Martin Luther King’s affairs and Eleanor Roosevelt’s lesbian proclivities.)

The other was Clyde Tolson (Armie Hammer,) a dapper young lawyer hand picked by Hoover as his Number Two man and as his closest associate.

Tongue-wagging Washingtonians have long speculated that Hoover and Tolson were homosexual lovers. Black’s screenplay (he won the Oscar for writing “Milk,” about iconic gay politician Harvey Milk) acknowledges this, but argues that we’ll never know for sure.

And in that ambivalence “J. Edgar” finds its greatest strength.

Black makes the case that Hoover was indeed gay. But he suggests that given his station and the times he lived in, the FBI director could never express himself sexually, especially after his mother, sensing his proclivities, declared that she would rather have a dead son than a “daffodil.”

And so the Hoover/Tolson relationship is here a tortured one. A deep friendship, certainly, but probably a platonic one with neither man daring to take it to a physical level.

And here’s the weird thing…while Eastwood’s film certainly presents Hoover as a bully, a schemer, a racist and almost insanely obsessed with what he saw as the threat posed by American leftists, it also views him as a tragic figure.

As a man who never experienced love.

Credit for the film working as well as it does largely can be laid at the feet of DiCaprio. After “The Aviator” (in which he played Howard Hughes), I shouldn’t have doubted the guy’s chameleonic abilities.

I can say here that five minutes into “J. Edgar” I wasn’t even aware that this was Leonardo DiCaprio. Granted, a huge chunk of the “performance” comes from an astounding makeup job that transforms the handsome “kid” into the jowly bulldog of Hoover’s maturity.

But there’s an awful lot to relish here…his vocalizations (clearly, he’s carefully studied Hoover’s style,) the insecurities masked by displays of arbitrary power, the desperate need for self-justification.

This is a performance of total immersion.

And he’s beautifully matched by Watts in a minor but essential role, and especially by Hammer (the Winklevoss twins in “The Social Network,) whose Tolson has the polish and ingratiating persona Hoover so desperately lacked.

(My one complaint about Hammer’s perf is his old-man makeup, which is as phony and distracting as DiCaprio’s is excellent.)

As is his wont, Eastwood tells his story with a minimum of look-at-me directorial flourishes. The guy is awe-inspiring.