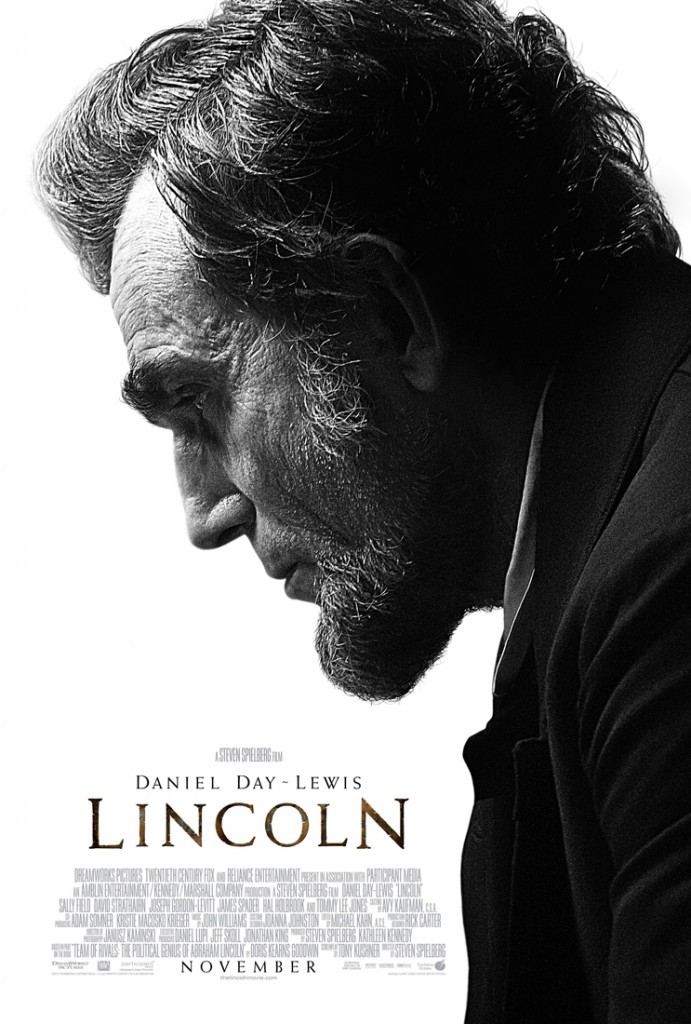

The first thing you must know about Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” is that in the title role Daniel Day-Lewis gives the performance of a lifetime.

Yeah, yeah, we’re all accustomed to Day-Lewis diving heart and soul into the characters he plays. But in “Lincoln” he outdoes even his own high standards. Two minutes into the film you no longer are even thinking in terms of technique and performance. Daniel Day-Lewis has vanished to be replaced by freakin’ Abraham Lincoln.

The second thing you must know about “Lincoln” is that it’s less a movie than an illustrated history lesson, that it is forever becoming bogged down in political discussions and declamatory monologues. There’s not much forward momentum. It comes perilously close (in at least this man’s opinion) to being a dramatic dud.

It’s Spielberg’s deal with the devil: one of the finest performances you’ll ever see in a borderline mediocre package.

Though ”Lincoln” is based in part on Doris Kearns Goodwin’s brilliant book “Team of Rivals” — about how Lincoln gently rode herd on his dissenting and oft-times disloyal cabinet members — Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner concentrate on a different story: the effort to ban slavery through passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution.

“Lincoln” contains a brief scene of chaotic fighting, but the real battle here is one of words and ideas.

The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863 was an executive order that freed the slaves in the rebellious Confederacy, but did nothing for those elsewhere in the country. To rectify this required passage of a new amendment, and now that he has won a second term Lincoln is rallying his political forces to ram the legislation through a reluctant House of Representatives.

The effort that will require subterfuge, sleight of hand, even duplicity on the part of the President.

It isn’t a simple or a pretty picture. “Lincoln” recognizes the complexity of popular thought about blacks and liberation in early 1865. Within his own party Lincoln had to contend with “radical Republicans” who advocated instant emancipation and the post-war punishment of the South; these firebrands angrily ridiculed the President for his “cowardly” foot dragging.

Mainstream Republicans were basically conservative on matters of race. They supported a war to preserve the union but clearly were not fighting for black equality, which both terrified them and seemed a violation of the God-given order of the universe.

And then there was a handful of House Democrats in full support of slavery and eager for an accommodation with the Confederacy to stop the slaughter.

Several narratives run through the film. To placate peace advocates Lincoln puts on a show of allowing Southern diplomats to enter the North to discuss a cease-fire. But so as not to outrage the radical members of his party, he cagily avoids meeting with the Confederates. Besides, he knows that unless they are guaranteed the right to own slaves, Southerners will continue with the war.

For too much of “Lincoln” characters speak not in dialogue but in political declarations. Happily, Spielberg and the Pulitzer-winning Kushner (“Angels in America”) periodically break away from the back room arm twisting to reveal small human moments. Spader, for instance, offers some blessed moments of comic relief as a cynical lobbyist.

Another story line centers on three operatives (John Hawkes, Tim Blake Nelson, James Spader) given the job of lobbying, wrangling, blackmailing and bribing members of the House to give the President the two thirds majority he needs. (You know what they say about laws and sausages…if you saw how they’re made you’d never touch them.)

Tommy Lee Jones steals his every scene as Thaddeus Stevens, leader of the radical Republicans, a sneering orator with a tongue like a buggy whip and perhaps the worst wig in Christendom. (The real Stevens, we’re told, had his wig cut equally all around so that he never had to worry about which side was the front and which the back.)

A subplot that never quite jells involves Lincoln’s son Robert (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), who is desperate to defy his protective parents and enlist in the Union Army.

Indeed, there are moments when “Lincoln” threatens to become an illustrated directory of the Screen Actors Guild. The cast is thick with familiar faces: David Strathairn (as Sec. of State William Seward), Hal Holbrook, Jackie Earle Haley, Jared Harris (as Ulysses S. Grant), Michael Stuhlbarg, Walton Goggins, Lee Pace, Gloria Reuben, S. Epatha Merkerson…the credits list more than 100 cast members.

But at its heart “Lincoln” has Daniel Day-Lewis, and that is enough.

Essentially this Lincoln is unknowable (an opinion held even by those who worked with him). But the film humanizes him. There’s a lovely scene when the President discovers his young son Tad (Gulliver McGrath) asleep on the floor in front of a White House hearth. Lincoln clears away the books and playthings, and lies down beside the child. The boy instinctively throws his arms around his father’s shoulders and, riding on his daddy’s back, is sleepily hoisted off to bed. It’s a lump-in-the-throat moment.

Day-Lewis taps all the sides of Lincoln we expect: storytelling raconteur, a melancholy plagued by memories of his dead son (Willie, 11, died of typhoid fever in 1862) and troubling dreams. Yet he also has the ability to motivate himself and others, to quietly (he rarely raises his voice) inspire and sway opinions. A man who thought big but retained the common touch.

Not particularly lovely, but pregnant with truth, is an argument between Lincoln and his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln (Sally Field), a woman who often seems on the verge of hysteria and who has been driven into a deep depression by Willie’s death. Field is really terrific, an intelligent woman who knows posterity will think of her as the President’s crazy wife but seems unable to control the roiling emotions that incapacitate her.

Individual moments in “Lincoln” work very well. But when it comes to the big picture, the film feels plodding and overlong. Still, Day-Lewis’ performance is one for the ages.