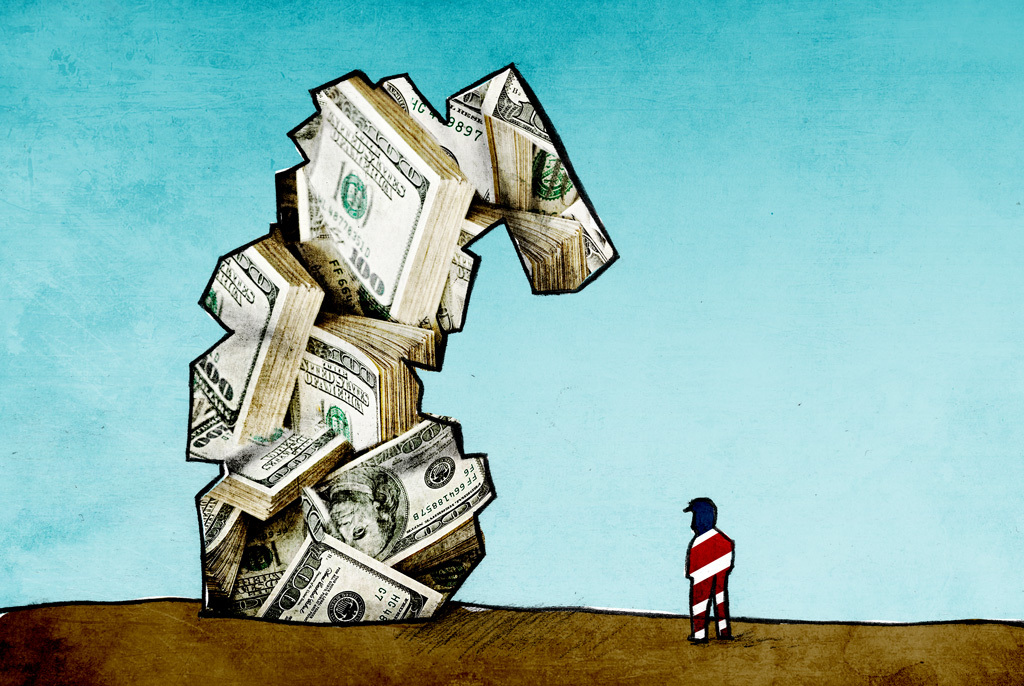

What has the U.S. achieved by pumping $60 billion — an average of $625,000 every hour — into Iraq to fix what the American invasion 10 years ago had broken?

Not all that much, according to the Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction (SIGIR), Stuart Bowen. The biggest American reconstruction project since the post-World War II Marshall plan was crippled by bad planning, fraud, corruption and outright theft.

So says a 174-page SIGIR report which comes to the conclusion that “as things stand, the U.S. government is not much better prepared for the next stabilization operation than it was in 2003.” Then, as now, there is no structure to integrate the various government agencies involved in rebuilding projects. Then, as now, there is no integrated data system to track money flows and contractors, says the report, the last of a series.

It is entitled Learning from Iraq but suggests that not all lessons have been fully absorbed yet. Some of the practices that bedeviled the effort in Iraq live on in Afghanistan, where U.S. troops will stay until 2014.

The report recalls the staggering amount of cash involved in the effort to rebuild the shattered country: “In 2003 and 2004, more than $10 billion in … cash was flown to Baghdad on U.S. military aircraft in the form of massive shrink-wrapped bundles of $100 bills stored on large pallets.” Once unloaded, the money was handed to contractors who hefted it away in duffel bags. “This money was not managed particularly well,” the report notes.

This is a polite understatement. A sizeable chunk of the airlifted cash has never been accounted for.

The original infusion of cash came from frozen or seized Iraqi assets held at the Federal Reserve in New York. U.S. taxpayers, through Congressional appropriations, chipped in another $60 billion. Critics of the U.S. endeavor In Iraq contrast the vast sums spent on infrastructure there with the lack of major infrastructure projects in the U.S. Then Secretary of State Colin Powell provided a counter-argument even before the U.S. went to war: “You break it, you fix it.”

What went wrong with the fixing is highlighted by statements from 32 U.S. and Iraqi officials Bowen interviewed for his report. Running like a red thread through Iraqi comments is the complaint that the Americans did not consult Iraqis, that there was no coordination between different U.S. agencies, and that the Americans did not pay enough attention to corruption.

Fuad Hussein, an aide to Kurdistan President Massoud Barzani, summed up many similar observations in blunt language: “Not only was there no coordination between the Department of State, the Pentagon and the CPA (Coalition Provisional Authority), they were fighting each other. I had two advisers — one from the State Department, one from the Defense Department; they didn't talk to each other.” Another factor that made working with the Americans difficult: “They knew nothing about the local culture.”

Claire McCaskill, a Democratic Senator involved in the oversight of the Iraqi reconstruction program, told the Inspector General that the various U.S. agencies and departments had worked at cross-purposes to such an extent that they formed “a circular firing squad” that guaranteed failure.

Poor planning, weak oversight and the absence of a single agency responsible for tracking how reconstruction money was used combined for an environment where fraud, waste and abuse flourished, in the words of Senator Susan Collins, a member of three of the Inspector General’s reporting commissions.

Bowen’s swan song — his office is to end operations in September — highlights a number of particularly egregious cases uncovered by SIGIR audits. For example: subcontractors for a Virginia-based company, Anham LLC, charged $80 for a small piece of drain pipe valued at $1.41 and a whopping $900 for a control switch worth $7.05.

Another legacy of the American reconstruction effort: abandoned projects started by U.S. agencies without consulting the Iraqis whether they wanted or needed them. Consequently, Iraqis felt no ownership and frequently walked away from projects, leaving them half-completed.

Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki, one of the officials Bowen interviewed for the report, reflected what appears to be a widely-shared view: the overall benefit of the American reconstruction effort was small in comparison with the large sums spent.

To avoid that kind of mismatch in future reconstruction programs, Bowen is suggesting that the government set up a new umbrella organization to ensure “unity of command and unity of effort.” That idea has yet to find enthusiastic backers in the administration.