Let’s admit at the outset that F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby” is above all else a literary masterpiece, which is to say that its power derives from the transformation of the written word into mental images and emotional reactions.

In short, the magic is all in our heads.

Let’s also admit that every effort to film “Gatsby” has, to a greater or lesser extent, failed.

The good news is that Baz Luhrmann’s new version fails less than most. In fact, there are moments when his “Gatsby” flirts with actually being good.

This could be a minority view. A recent advance screening of the film ended with at least one audience member – probably a fellow critic — loudly booing Luhrmann’s efforts . Audiences in my neck of the woods are notorious polite; in 40 years of reviewing this was a first.

There were moments in this film, particularly in the early going, where I was tempted to boo, too … or at least roll my eyes and brace myself for the worst.

But despite some missteps and overstatement, LuhrmanGatsbyn’s “Gatsby” accomplishes something other film versions haven't. It makes the mysterious Jay Gatsby a recognizable human being — not just a symbol of American upward mobility and can-do determination, but a flesh-and-blood figure of real yearning and pain and hope.

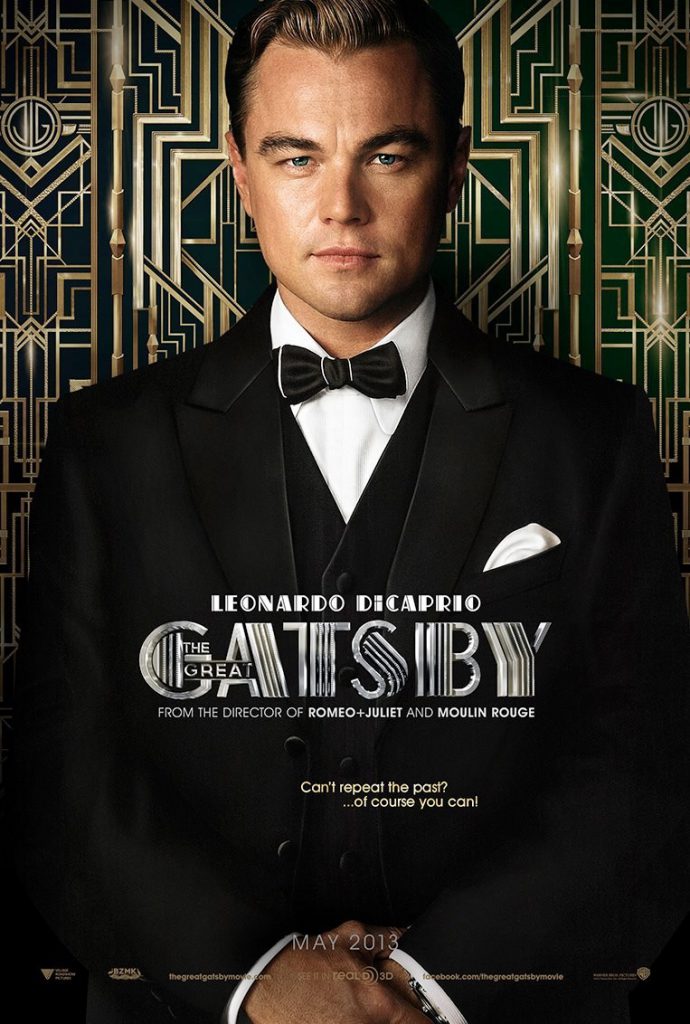

Second, this “Gatsby” works because Leonardo DiCaprio is so good in the title role.

This happens for two reasons. First, after a breathless, bounce-off-the-walls opening hour, Luhrmann slows things down, lets his story breathe, and lets the feelings of Fitzgerald’s story to come through.

Unlike Robert Redford’s stiff misfire in the 1974 version, his Gatsby is someone we can identify with, an individual undone by his emotions, a man enslaved by an impossible love, a mix of cool confidence and desperate insecurity.

The key is vulnerability. DiCaprio zeroes in on Gatsby’s childlike aspects. Here’s a character who has achieved incredible wealth and worldliness (apparently through criminal enterprise) but who remains a love-struck adolescent when it comes to the woman who got away. DiCaprio’s Gatsby is simultaneously naïve and foolish and weirdly heroic.

DiCaprio is so good that the film flounders when he’s not onscreen … which is the first 30 or so minutes.

That’s when we’re introduced to our narrator, bland Wall Street bond salesman Nick Carroway (Tobey Maguire), his cousin Daisy (Carey Mulligan) and her brute of a polo-playing husband, Tom Buchanan (Joel Edgerton).

Nick has managed to rent a house on Long Island next door to the castle-like abode of Jay Gatsby, a reclusive millionaire (and alleged gangster) who throws unbelievably lavish parties. Daisy and Tom live across the bay on the “right” side of the tracks, as it were.

Luhrmann and his co-writer, Craig Pearce, take some big chances here. They’ve invented a bookending device in which Nick is drying out in a sanitarium for alcoholics. Part of his therapy is to write a journal, and his jottings become the story of Gatsby and the happenings which, evidently, drove the former tea totaler to drink.

Periodically we return to Nick’s therapy sessions with a kindly shrink (Australian acting great Jack Thompson, all but lost in a nothing role); unfortunately, these passages bog down the real story, that of Nick’s friendship with Gatsby and the latter’s doomed love for Daisy.

Moreover, Luhrmann gets cute by having Nick’s written words materialize on screen, swirling around him like cigar smoke. It’s a way to get Fitzgerald’s writing into the movie, sure, but it’s almost painfully literal.

And there is absolutely no reason why this film needed to be in 3-D. It’s not only unnecessary, it’s a distraction.

Much has been made of Luhrmann’s love of visual excess (i.e., “Moulin Rouge”) and his use of modern hip-hop behind “Gatsby’s” cacophonous Jazz Age party scenes. But the frenzied kineticism the filmmaker brings to these bacchanals is really quite appropriate; they’re all about drunken chaos, after all, and the modern music has been so skillfully blended into the overall soundscape that it doesn’t sound anachronistic.

Occasionally Luhrmann’s zeal for zip goes overboard. Gatsby and Tom Buchanan drive souped-up roadsters that fly down Long Island’s two-lanes with the roar of jet fighters … these sequences are heavy on CGI and in fact feel a bit cartoonish, like outtakes from “Speed Racer.”

Indeed, the film’s reliance on computer-generated settings gives it an unreal feel which I found more offputting than magical.

Even before DiCaprio makes an appearance we (along with Nick) are hijacked by the cheating, overbearing Tom and taken to a Manhattan hotel suite for a boozy revel with Tom’s tawdry mistress Myrtle (Isla Fisher) and a couple of cliché-spewing flappers.

About this time you’ll feel you’ve stumbled into a meeting of Overactors Anonymous.

And in her first appearance, Mulligan’s Daisy seems too simpering, too wan, too spoiled and empty-headed to be anything but maddening. Of course this is the problem with “Gatsby” … its heroine is unworthy of the devotion showered upon her.

The good news is that once on the scene DiCaprio raises the game of everyone around him. Daisy becomes weirdly lovable, Tom seems less creepy and more substantial (he squares off with Gatsby for a terrific confrontation late in the picture) and Maguire’s Nick becomes less the impartial observer and more a young man seriously disturbed by what he sees going on around him.

Luhrmann’s “Gatsby” is far from perfect. But it captures the subtle shadings of this unfilmable book better than any other cinematic treatment. It may not be triumphant, but it’s a worthy effort.