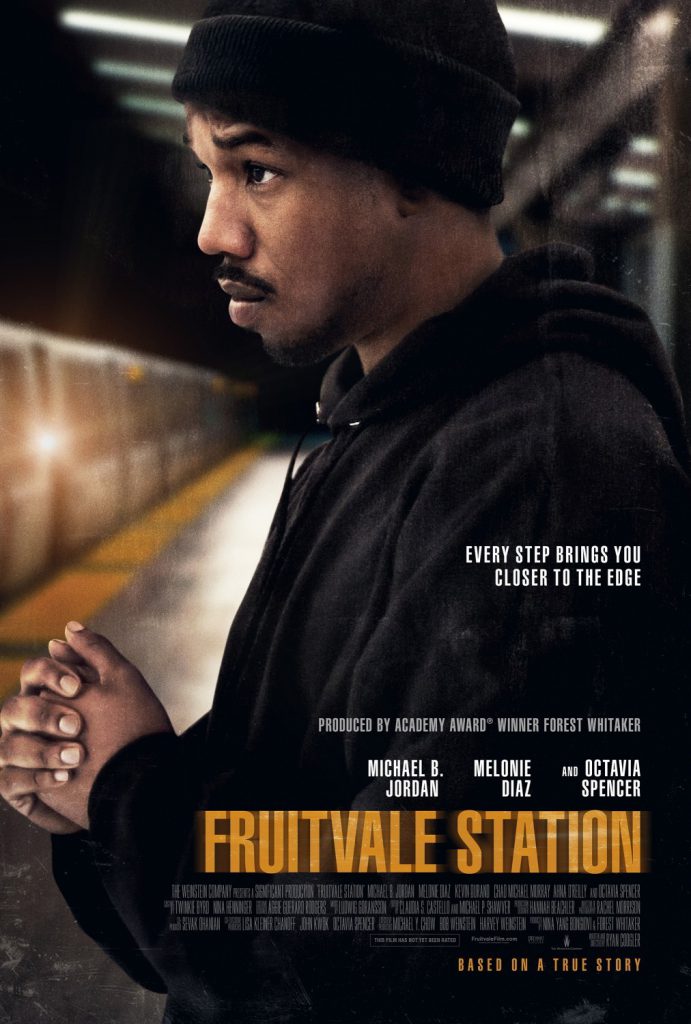

If “Fruitvale Station” was concerned only with a young man’s death on an Oakland train platform early in the hours of Jan. 1, 2009, it would be hard going, indeed.

But Ryan Coogler‘s stunning writing/directing debut is less about dying than about living, and by attempting to limn the world of one individual it becomes the story of an entire class of contemporary Americans.

“Fruitvale Station” was inspired by the shooting by a Bay Area Rapid Transit cop of 22-year-old Oscar Grant. I’m giving nothing away by letting you know that Oscar dies. It’s the first thing you see in the movie.

In grainy cell-phone video — Is this real footage or a re-enactment? Can’t tell — we see transit police officers standing over several young black men sitting with their backs against a wall of the Fruitvale BART station. A ruckus breaks out and the cops jump on one of the young men, who is lying on the concrete. We hear observers yelling at the officers to stop. Suddenly there’s a gunshot.

The film proper begins almost 24 hours earlier. Oscar (the Oscar-bound Michael B. Jordan), his live-in girlfriend Sophina (Melonie Diaz) and their pre-school age daughter Tatiana (Ariana Neal) are waking up on Dec. 31, 2008.

Oscar and Sophina are having a quiet early-a.m. argument. Oscar has had sex with another woman. He says it only happened once. No, she says, you only got caught once.

But Oscar swears fidelity, says he wants nothing more than to spend the rest of his life with Sophina and little Tatiana, in whose presence he becomes the playful, loving and responsible Daddy.

We follow Oscar through his day. He goes to a grocery story to buy food for a big birthday bash that night for his mother, Wanda (Octavia Spencer). While there he begs his former boss to give him back his job — he was fired two weeks earlier for being regularly late for his shift.

“Do you want me selling dope?” the desperate young man asks the manager, who has already filled Oscar’s old position and cannot rehire him.

He hasn’t told Sophina that he’s out of work.

Out on the street a speeding car run down a stray dog. Oscar holds the animal until it gives a final shudder.

That night, with little Tatiana safe at her aunt’s house, Oscar, Sophina and friends take the train into San Francisco to watch the New Year’s fireworks. On the way back there’s a delay and the group turn the car into a nightclub with a pair of battery-powered speakers and an iPod. Everyone — black, white, gay, straight — boogies down.

Like a square dance in a John Ford film, it’s a diverse community suddenly coming together.

And all the while they’re getting closer to Fruitvale Station.

Hearing this plot recap, you might assume that until its final, gut-wrenching last act nothing much happens in this movie. To the contrary, everything happens. As I said earlier, it’s about life, about the world this one young man inhabits.

But like all great art, it’s about more. It’s a humanistic portrait of the new urban America, where even those who have a job are only a paycheck away from a homeless shelter, where long-term (hell, even short-term) security is as impossible a dream as a trip to the moon.

It’s about a world where everyone is on the cusp of poverty, where you never turn down a double shift. Yet these characters still find a way to love, laugh, and celebrate.

What Ford did for the Dust Bowl Okies in “The Grapes of Wrath,” Coogler does for the 21st-century urban underclass. Think I’m exaggerating? Watch this film.

There is absolutely nothing here that would let you know that Coogler is a first-timer. The writing, the intimate camera work, and especially the performances are little short of spectacular.

Individual scenes unfold with the rhythms of great stage writing, with conversations circling around a subject, taking a brief detour, and then returning to nail the moment.

And some of these moments will stick with you. A flashback showing Wanda visiting Oscar in prison (yes, he’s an extremely complex figure) is heartbreaking and terrifying. And a New Year’s sidewalk conversation with a stranger (both of their women have gone inside a shop to use the bathroom) becomes a simple but heartfelt reverie about fatherhood.

The performances? From top to bottom they are astonishing.

Jordan, a young actor whose career I have been following for several years (mostly on TV shows like “The Wire,” “Parenthood” and “Friday Night Lights”), gives us an Oscar who is far from perfect but whose heart is in the right place. He’s really trying to do good by his woman, his child, and his extended family.

This kid has terrific acting chops, yes, but he’s also got something you can’t learn. He’s got charisma, he’s got depth, he’s got soul. It’s all up there on the screen.

Spencer, already an Oscar winner for “The Help,” takes a typical mother role — religious, an authority figure — and wrings every bit of feeling out of it.

Diaz is another major find, bringing Sophina to vibrant life with an unforced naturalism that is a revelation. And I’m reluctant to call little Ariana Neal a child actor — it seems too patronizing for this little girl who underplays her role so beautifully. She’s a great actor. Period.