In October 1967, when I was an Air Force chaplain’s assistant in England, I helped organize a pilgrimage of Catholic airmen to Rome. The itinerary included visits to major statuary, crumbling ruins, and St. Peter’s Basilica.

As it turned out, only one other airman – a six-and-a-half foot tall Minnesota Lutheran named Moose – joined me on the tours. The other 30 guys disappeared on Fernandina Beach, and we didn’t see them until they showed up at the airport on the last day, sunburned and sated.

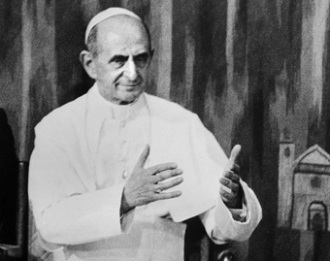

Moose and I didn’t skip a single opportunity on the itinerary. The day after our arrival, a Sunday, we stood in Saint Peter’s Square to watch Pope Paul VI bless the crowd. It was an exotic moment for two sheltered American Protestants.

We stood next to a huge speaker when the Pope spoke, so his nasally voice sounded like an air horn. He addressed the crowd in Italian for several minutes as we held our hands over our ears.

An old woman in the crowd told us to find something to lift up when the Pope started speaking in Latin.

“That’s the blessing,” she said. “It covers anything you want.” As an example, she showed us a small golden crucifix.

She held the crucifix in air and closed her eyes prayerfully when the Pope began the blessing. Moose and I reached into our shirts and pulled out our dog tags, lifting them as high as the chain would allow. It probably looked like we were sniffing them.

The next day, Moose and I found our way to a Vatican courtyard where the pope was receiving a smaller crowd. The tour agent told us the courtyard would fill up quickly, so we got there early and waited beneath a small balcony.

It was difficult for people to slip ahead of Moose, who stood tall and implacable, unwilling to give up his space to see the pope close-up. But a short, stout nun, followed by a half dozen school girls, pressed her large bosom against Moose’s arm and he flushed and jumped aside. The nun did the same thing to others in front of Moose and soon she and the school girls were in the front row.

Even so, Moose and I were fairly close to the window and when the pope emerged we could see the crinkles around his eyes.

The Pontiff, a fair linguist, began to address the crowd in different languages. “Français,” he announced, and when the French speakers applauded, the pope lifted his right hand to his ear and made a giggling sound. “Português,” and when persons from Portugal applauded he giggled again. Soon, he announced, “English,” and after his giggle he offered a thickly accented greeting to the English speakers.

“That was neat,” Moose said as the crowd dispersed. “We got closer to the pope than we ever get to the chaplain.” That was true, because when the chaplain mounted the pulpit, the airmen retired to their desks to drink coffee.

We saw Pope Paul one more time that week, on October 28, when he stood at the main altar of St. Peters next to the Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras I.

The Pope and the Patriarch had already met in 1964, ending a centuries old rift between the western and eastern churches. The October visit was a follow-up, an auspicious occasion when the two church leaders were to join in a concelebrated mass.

For us uninformed Protestant boys, the pair looked mismatched at the altar. The Patriarch with his long beard towered over the petite pope.

But Moose and I knew it was a major historic event because the basilica was filled with ecclesiastical celebrities. Included in the procession was Bishop Fulton J. Sheen, known to Moose and me as the “Uncle Fultie” of 1950s television fame. Sheen, like the American politician he was, kept straying from the procession to shake hands, repeating, “How are ya, how are ya…” For years, shaking Bishop Sheen’s hand was my most vivid memory of the day.

Years later I began to realize what an important day that had been, when a historic split in the Christian church began to mend. At the end of Athenagoras’ visit to Rome, the Patriarch and the Pope issued a joint statement, thanking God “for enabling them to meet once again in the holy city of Rome in order to pray together with the Bishops of the Synod of the Roman Catholic Church and with the faithful people of this city, to greet one another with a kiss of peace, and to converse together in a spirit of charity and brotherly frankness.” (See )

And years after that, when I was on the staff of the National Council of Churches, I reminisced about this day in October 1967, and said it was probably the most historic event I had ever attended. “It was,” I told colleagues who might have missed it, “a concelebrated mass by the pope and the Patriarch.”

But my friend Father Leonid Kishkovsky, ecumenical officer of the Orthodox Church in America, raised his hand.

“It was not a concelebrated mass,” he said quietly. “Where did you get that?”

“That was what they told us,” I said. “I was a 21-year-old Baptist. There’s no way I could have made the word up.”

Leonid shook his head gently. “It was not,” he repeated. “It couldn’t have been.”

There is no one on earth better informed about interchurch relations than Leonid Kishkovsky, so I will take him at his word.

But I will never forget that in October 1967, Moose and I saw Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras I stand side by side at the central altar in St. Peters Basilica.

And what ever they were doing together that day, it was for us an incomparably historic event.