“Life Itself” is about a man redeemed by love.

Of course it’s about a lot more than that. Its subject is the late Roger Ebert, the world’s most famous movie critic — hell, the most famous critic in any discipline — and it follows his career from high school journalist to Johnny Carson regular and on to his development as a one-man publishing empire and his death last year after a long and crippling battle with cancer.

That’s the public Ebert. But the emotional narrative that emerges from Steve James’ wonderful documentary is that of a borderline raging egoist who late in life met the right woman and discovered his softer, more humane side, spending his last years basking in the glow of extended family and relishing his role as step-grandpa. It’s the Roger Ebert we never knew until now.

This film is a profound and deeply moving portrait not just of a great thinker and communicator, but of a brave and — at long last — caring man.

James — whose 1994 documentary “Hoop Dreams” was championed by Ebert and his TV partner, Gene Siskel — was invited by the critic and his wife Chaz to spend time with them in order to produce a documentary based on Ebert’s 2011 memoir Life Itself. James had barely gotten started on the project when Ebert died in 2013.

But James forged ahead, using what little original footage he already had, combining it with archival material and the recollections of Ebert’s friends, family, colleagues (critics like A.O.Scott, Richard Corliss and Jonathan Rosenbaum), as well as famous filmmakers — Martin Scorsese (a producer of the doc), Werner Herzog, Errol Morris — whose careers were advanced by his perceptive and appreciative reviews.

The resulting film is funny, eye-opening, and inspiring. It’s going to score mightily when awards season kicks into high gear.

Ebert was an only child who early on found journalism “unspeakably romantic.” As a teen he wrote and distributed his own newspaper in his Urbana, I.L. neighborhood. Landing a job at The Chicago Sun-Times, he worked all kinds of gigs before being named the paper’s movie reviewer in 1976. (An old colleague described him as “tactless, egotistical and a showboater…but already a great writer.” Another remembered Ebert as “a nice guy — but not that nice.”)

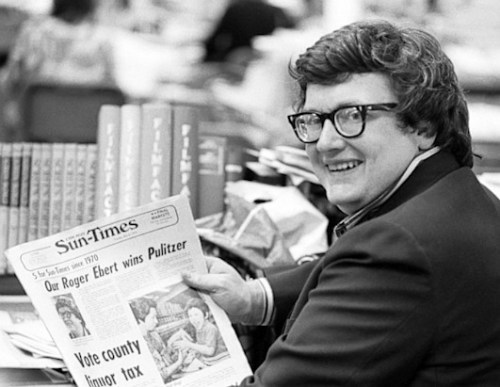

Back then movie review slot at major newspapers was often viewed as the last gasp of a formerly great newsman. Ebert, though, revitalized the profession, in 1975 becoming the first film critic to win the Pulitzer Prize.

After that other papers came calling. Ben Bradlee was determined to lure Ebert to The Washington Post, offering an outrageously lavish salary and working conditions. Ebert turned down the job, telling friends “I’m not going to learn new streets.”

At one point Ebert branched out from just reviewing films to creating one. He penned the screenplay for Russ Meyer’s 1970 sexploitation film “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls.” Asked why Ebert would get involved in such a tacky project, his friends — without missing a beat — answer “Big boobs.”

After a day at the office, Ebert became something of a wild man. Old drinking buddies recall a barfly who could hang tough until the wee-hours closing, and then move on to a place that stayed open until 4 a.m. He was an epic storyteller — he seems to have viewed conversation as a competitive event.

Occasionally Ebert showed up with a hooker as his “date.” Testifies one drinking buddy: “He had the worse taste in women of any man I’ve ever known.”

In 1979 Ebert realized his drinking was getting out of hand. He gave up the bottle and joined AA.

A large part of the film is devoted the contentious relationship of Ebert and The Chicago Tribune‘s Siskel, who regularly saw each other at screenings but who were so competitive they barely spoke to each other for the first five years of their aquaintance.

“Life Itself” has some delicious revelations about Siskel, who as a young man was a regular member of Hugh Hefner’s retinue — we see a photo of Siskel in a hot tub with a topless Playmate.

“Roger wrote ‘Beyond the Valley of the Dolls’,” observes a friend of both men. “Gene lived it.”

Siskel, who had an Ivy League education, resented Ebert’s Pulitzer and on occasion played practical jokes that exploited Ebert’s unfettered self-esteem. Ebert liked to lord his success over his on-air partner. Those who knew them both said much of the rancor came from Siskel’s refusal to be pushed around by his colleague: he was “a rogue planet in his” — Roger’s — “solar system.”

Occasionally Ebert’s behavior was simply boorish. Siskel’s widow, Marlene, recalls the time she was seven months pregnant and Ebert “stole” the taxi she had flagged down.

But their TV show — with its “thumbs up” rating system — was a hit first on public television, then syndicated around the world via the Walt Disney Company. Siskel & Ebert could make or break a film and revive careers.

“Life Itself” makes clear that the two critics were sometimes barely able to tolerate one another. An extended outtake of them berating each other while trying to tape a promotional spot makes them look like two petulant kids fighting over a toy.

But the show was a hit, demonstrating that even critics disagree. Sometimes violently.

Ebert’s life changed when he met his future wife, Chaz, at an AA meeting. This woman, he wrote, saved him from “a life of lonely decrepitude.”

It was an unusual pairing. He was a single child, and white. She was an African American from a big family.

Theirs was a love story for the ages, one that had such a deep effect on Ebert that in many essential ways it rewired his personality.

“Life Itself” doesn’t shy away or attempt to sanitize Ebert’s final illness — which cost him his lower jaw and his ability to speak, eat, and drink. James captures the critic during a long hospital stay, and the indignities of Ebert’s illness are often difficult to watch.

But Ebert — who by this time was communicating through a laptop computer outfitted with a voice synthesizer — rarely appears to be sorry for himself. And the love and care provided by Chaz and her family is inspiring.

It was a full life. We should all be half as lucky.