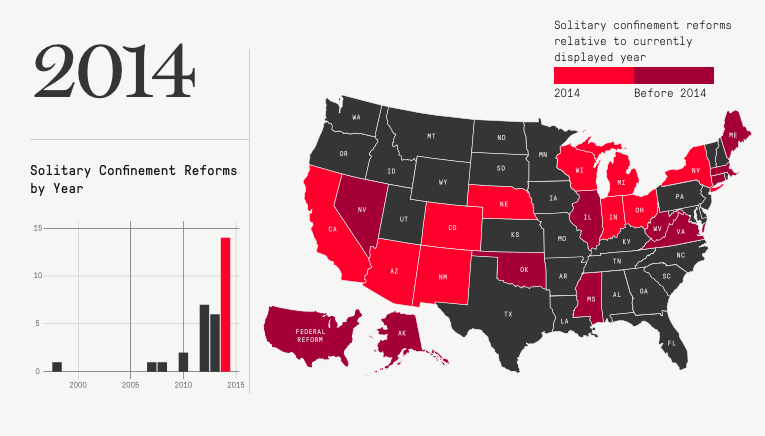

As the year ended, The Marshall Project provided a comprehensive roundup of reforms to solitary confinement practices across the country. Eli Hager and Gerald Rich write: “In 2014 one of the most controversial practices in criminal justice, solitary confinement, faced unprecedented challenges. As a result of legislation or lawsuits, ten states adopted 14 measures aimed at curtailing the use of solitary, abolishing solitary for juveniles or the mentally ill, improving conditions in segregated units, or gradually easing isolated inmates back into the general population.” The article goes on to describe each of the measures adopted in 2014, and in several previous years.

Reform is not synonymous with abolition, and the forms it takes are almost always incremental. These changes have, or will, improve the day-to-day lives of perhaps several thousand individuals who have been suffering in solitary. The reforms stand as a tribute to the thousands of activists and advocates — including many currently or formerly held in solitary confinement themselves — who have worked to bring this domestic human rights crisis to the attention of the nation after it had languished in the shadows for decades.

Still, it’s worth noting that this “Shifting Away from Solitary” has not been a seismic shift, and to date has affected only a small number of the more than 80,000 individuals who, according to the best available data, are in isolation in the nation’s prisons on any given day.

For example, in California — which is second only to the federal prison system in the use of solitary confinement — about 6,000 people are in solitary confinement, with thousands more locked down in double cells. Of these, 400 have qualified for a pilot program to transition them back to the general prison population, and 150 have actually made the transition.

In many other states, the focus has been on children under the age of 18 in adult prisons, or people with mental illness. These are both highly vulnerable groups, and the latter is in many states quite a large group as well, and their removal from solitary is significant. It also demands some scrutiny, since many are being moved to new special units with problems of their own.

All such reforms also risk dividing the incarcerated into two groups — those who “deserve” to be in solitary confinement, and those who do not. For advocates who believe that solitary is a form of torture, and therefore not acceptable for anyone, the road ahead remains a long one. So, too, for opponents who object to solitary as a “sentence within a sentence,” handed down by prison officials without due process of law — since these same prison officials are usually involved in initiating, negotiating, or formulating the reforms.

Despite such reservations, there is ample change to fortify enemies of solitary for the struggle ahead. For decades, the use of solitary confinement grew with a virtually complete absence of attention from the media, policy makers, and even major activist groups. It depended upon its own invisibility to sustain itself. To penetrate the walls of secrecy and ignorance surrounding solitary confinement is only a first step — but it is one that can never be undone.

Jean Cassella contributed to this article.