My brother and I woke to the sound of our father banging on our bedroom door. “Good heavens, here we are in the middle of a military coup d’état and you boys are sleeping through it.” So started one of the more interesting fortnights of my life.

My brother and I were both in college in the States while our father was the American ambassador to Iraq. We were spending the summer of 1958 with our parents at the embassy in Baghdad.

We went to a window that overlooked the front grounds to see what was going on and were stunned by something you do not often see: a battle tank rolling past the grounds and Iraqi soldiers manning several machine guns encamped on the front lawn. (We were told later that the troops were there to protect us from possible mobs, but the machine guns had better fields of fire toward us rather than toward potential mobs.) We were in the middle of the July 14, 1958, coup d’état that left the monarchy in Iraq dead and the military in power proclaiming the Republic of Iraq.

Nobody saw the coup coming. Political unrest was widespread in the Middle East, and civil war was pending in Lebanon. Iraq was generally assumed to be reasonably calm, so nobody knew that a large portion of the army was unhappy and planning to revolt given an opportunity.

As governmental policy in Iraq at the time aimed at lowering the possibility of armed insurrection, ammunition was not routinely issued to the army; furthermore, large numbers of military were not based within striking distance of Baghdad. However, the situation in mid-July 1958 was unique. Fearing that the impending civil war in Lebanon would erupt and spread to Jordan, the king of Jordan asked his relative, the young King Faisal II of Iraq, for help.

In response, several Iraqi army brigades were repositioned from Basra in the southeast to near Jordan in the west. The troops were scheduled to spend the night at a base just outside Baghdad and were issued ammunition in preparation for potential combat the next day or so. Unexpectedly having their troops armed and within striking distance of Baghdad provided the opportunity the conspirators were waiting for. The coup was launched early in the morning of July 14 — Bastille Day.

The first word of the coup the embassy, or for that matter, the world, had was a telephone call from a Foreign Service officer who lived near the palace on the other side of the Tigris River from the embassy. As was a common custom in summer in the Middle East before the advent of modern air conditioning, he was sleeping in the open on his flat roof where he was exposed to all the night sounds of a busy city. This day the sound of gunfire near the palace woke him early in the morning. He telephoned in to the embassy and woke Dad with the first news anyone had of the coup.

As the day progressed, reports of horrendous atrocities came in. Troops were murdering the royal family and anyone loyal to the monarchy, and mutilating their bodies. People were selling picture postcards of Iraqis playing soccer with the king’s head. Bloodthirsty mobs were roaming the streets.

My brother and I don’t remember any sense of fear. I don’t know if that was because of our naivety or the calm, in-control aura our father, the ambassador, exuded. I do remember when my brother’s college roommate, who was spending the summer with us, started off to the local country club for a scheduled tennis game in the middle of a military coup. He seemed surprised at being turned back by the Iraqi military guard at the embassy compound’s gate.

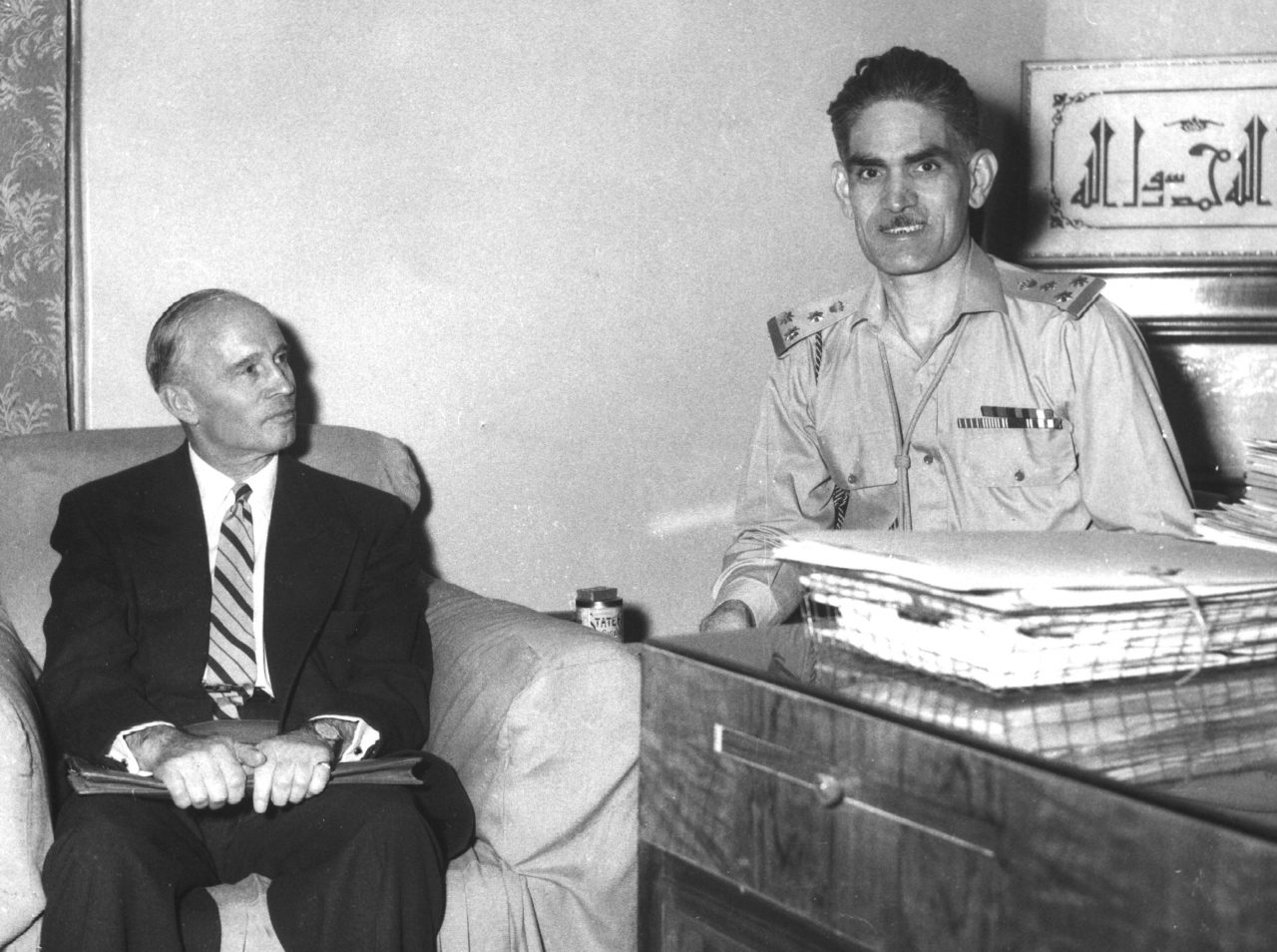

I also remember Dad going off to meet with the leader of the coup, Brigadier Qasim, during the first or second day of the revolution. Off he went — no convoy, no SUV and no guard. Just the embassy limousine with American and ambassadorial flags flying. He gave no indication that he felt anything could go wrong. In his mind, foreign diplomats, especially American Foreign Service officers, lived on a plane of existence somewhat above the world’s masses. That being said, a couple of days later when he was on a diplomatic outing somewhere in the city, Dad almost got caught by an anti-American street mob, escaping only because of the chauffeur’s skill of executing a bootlegger’s turn.

The Marine embassy security guard force donned combat fatigues and set their machine gun emplacements on the embassy roof as soon as it became clear that a military coup was underway. Almost as immediately, Dad, being much more inclined to diplomacy than force, became concerned that the Marines, most of whom were barely past their teenage testosterone years, might be trigger-happy, so he had them stand down. This was probably a stroke of genius as later in the day we noticed Iraqi reconnaissance flights over the embassy probably looking for troop emplacements and radio gear.

American families started turning up at the embassy compound seeking safety from the mobs. Fires were started in 50-gallon oil drums to burn classified documents in preparation for the possibility of being overrun by the mobs or troops. That job ended up taking several days. Fortunately, the embassy was not overrun and no documents were compromised.

A mid-level Iraqi government official showed up at the embassy seeking asylum, which was granted. He stayed hidden in the embassy for several days until it was decided that letting him stay imposed too great a danger to the Americans who were sheltered at the embassy. He had to leave. Figuring that he would be safe if he could get off the embassy grounds, a plan to smuggle him out past the Iraqi guards was developed. The plan involved dressing him up as the chauffeur, complete with a mustache my brother painted on with a black marker, and letting him drive the limousine while the real chauffeur rode in the back seat pretending to be an American diplomat on official business.

Once away from the grounds the official would be dropped off and the real chauffeur would get back into uniform and drive back to the embassy. It all depended on the guards at the gate being more concerned with the passenger than with the driver, not recognizing the official’s fake mustache, and not recognizing the person in the back seat as the real chauffeur. Thank goodness it all worked.

The rebels required the embassy to decommission the radio that provided our only contact with the State Department. This would have isolated us from the United States had it not been for the backup radio in one of the compound’s outbuildings. Much to our distress, two days after the main radio was decommissioned, an Iraqi army officer appeared at the embassy door demanding our backup radio. The quick-thinking duty officer hauled out a portable rig that may not have been in working condition and handed it over hoping the subterfuge would not be noticed.

Dad’s very next cable to the State Department explained the problem and pleaded that nobody admit we still had radio contact. We would be in severe distress if the Iraqis took away our remaining radio. Of course that evening on the news, the secretary of state announced that he was still in touch with Baghdad — just what Dad had warned against. We cringed. Fortunately, nothing bad happened. By a stroke of good fortune, the Iraqis did not seem to pick up on the fact that we had the luxury of radio communication throughout the crisis.

The situation in neighboring Lebanon was a significant concern. In response to growing unrest unrelated to the situation in Baghdad, President Eisenhower landed U.S. Marines on the coast of Beirut the day after the coup in Iraq in a largely symbolic show of support for the embattled Christian president of Lebanon. Our first concern in Baghdad was whether this was an indication that a much larger conflagration would develop in the Middle East with us right at the middle. In addition, the State Department offered us some of the Marines from Beirut if we needed them for protection.

It was not clear just what we would do with the troops, especially as Qasim was trying to convince the world that he meant Americans no harm. We did not want Eisenhower deciding that we needed to be saved. We did not want a column of U.S. Marines advancing by force along the main highway from Beirut right past the embassy. That was one event I really did not want to have a box seat for. Fortunately, Lebanon stayed relatively peaceful, and the Marines did not move into Iraq.

One of the first things Dad discussed with the coup’s leader was evacuating American women and children and “nonessential males” from Iraq. At first Qasim did not want to let anyone leave as he wanted to maintain an image of protecting Americans, but he eventually relented, possibly influenced by the three American tourists who had been killed in Baghdad by anti-foreigner mobs.

Pan Am was hired to provide a shuttle between Baghdad and Rome. The entire evacuation took two weeks as many Americans needed to be evacuated with only one or two planes. Moreover, the logistical difficulties assembling Americans from throughout Iraq and getting them to the Baghdad airport were formidable.

We were on the last evacuee flight out of Baghdad. It would not have been proper for the sons of the ambassador to get special treatment. And my mother needed to stay as long as possible to fulfill her role as leader of the American community as long as there was any community in Baghdad. I spent the rest of the summer in Rome, where I got to know and party with the daughters of William Wyler, who was directing the blockbuster film “Ben Hur” in Rome. We three boys went home to the States and then to college at the end of the summer.

Mom stayed on in Rome as long as Dad was in Iraq. Dad was reaccredited to the Republic of Iraq as ambassador and stayed on in Iraq until the end of 1958, at which time he was appointed director of the Foreign Service and transferred stateside.