I was born in 1925 in the Ukraine. I remember often being hungry as a child. I wasn't alone; almost everyone was hungry during the Russian takeover of the government, and again when the German army occupied the country, because they shipped away our grain. The German army also took away many Ukrainians and forced them to work in Germany.

I and my young male friends were conscripted into a labor battalion and forced to work on the farms. Young women were also conscripted. We sometimes saw them working in the fields near us. Life on the farms was not too bad. We were fed well. I became quite handy with a scythe cutting grain.

Then we were shipped to the war zone and attached to a German army engineering unit. The work was hard and the days were long. We did many things: repaired airplane landing strips and damaged bridges. We were usually some distance from the battle zone. We were commanded by a tough old sergeant, and we soon learned that if we worked hard and gave him no trouble he was fair with us.

In the spring of 1945 the unit we were attached to was in northern Italy near Austria, being driven back by the U.S. Army. We knew only a little of what was really happening in the war, but it was no surprise to learn one day in May that the war there was over. The Germans had surrendered!

Immediately there was chaos everywhere, but at least there was no fighting. The German troops milled around, and in a few days were trucked or walked away. Our commander, Sergeant Meier, disappeared without a goodbye.

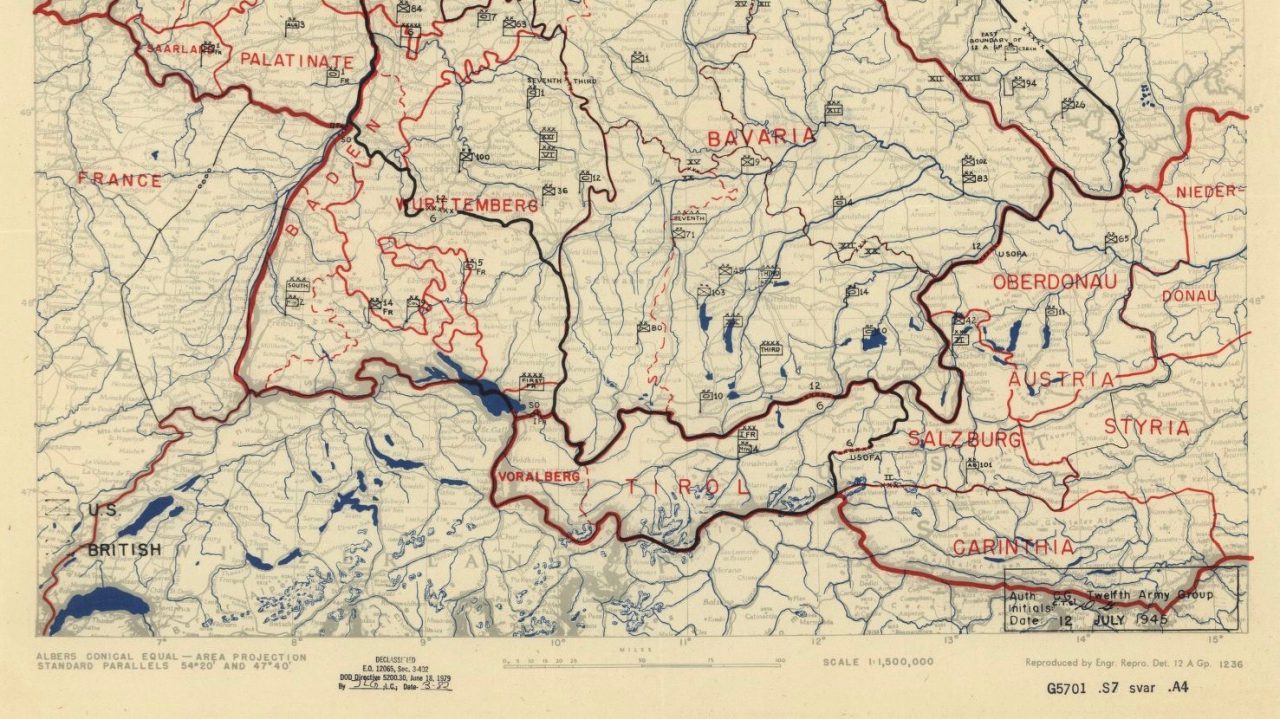

We were lucky to find ourselves in the American zone. Our group was visited by an American officer in a Jeep, who spoke to us in Russian and told us that according to the Yalta Agreement we would be returned to Russia. He told us that we would first be taken in a few weeks into Austria and the Russian zone of occupation. Meanwhile we were moved to an American camp, given U.S. Army Class B uniforms, fed old U.S. Army “C” rations and slept on army cots in army tents under army blankets. Not bad for refugees.

Finally the trucks came, and we spent two days driving to a military post near Graz, Austria, where we were turned over to the Russians. Then we feared we would begin a long trip to Siberia — on foot.

In all those months since leaving Ukraine I had not heard from my family. The only information that we received was by word of mouth. It was untrustworthy, but it was all there was. We were told the Ukrainian soldiers who had been taken prisoners by the Germans were all assumed to be traitors for not fighting to their death — the same as Russian soldiers. They were sent to Moscow, where they were sentenced to 25 years of hard labor in Siberia.

I shared this information with my friend Ivan. We decided we would take our chances and try to get to the American zone. We learned that to reach the Americans we would have to cross the western part of the Russian zone in Austria and then part of the British zone — a distance of 300 miles. This would be mostly through farm country and all on foot — and, while in the Russian zone, all in hiding.

Our only plan was to head west, farm to farm, barn to barn. We climbed into the hay lofts after the lights went out in the farmhouses. Our only resistance was from farm dogs who barked when they detected us, but fortunately never approached us.

We actually were spotted by many of the Austrian farmers who proved to be friendly and helpful — their way of sticking it to the Russians! One told us to be careful crossing the next farm — “He’s a communist!” I’ll be forever grateful to the farmer who went into his house to get each of us a hefty slice of bread spread over with butter. Except for a stolen egg or garden vegetable, it was the only food we had in the five days it took us to cross the Russian zone.

When we reached the last village in the Russian zone, it was a very busy place and we could see lots of Russian soldiers. A farmer told us there was no other way to get to the British zone but to cross the bridge in that village. He said he would help us, however, and that we should wait until he told us to go.

We worried that he was betraying us. But he sent us down a street on which the bright setting sun shone into the faces of those approaching us, and on the opposite side of the street, we were in the shade and difficult to see! As soon as we left the village we were greeted by British soldiers at a gate to the British zone.

We soon learned that for Ukrainians like us to get to America, in fact to even get into the American zone, we would have to be asked. We spent hours in long lines being interviewed by representatives of the allied countries but were never chosen. We felt lucky to be away from camp when a French representative interviewed refugees to settle in French Morocco.

Finally we were chosen to go to America under “President Truman’s law.” Our health was checked and found OK; we had no criminal record, and there was a job and shelter ready for us in the United States.

Labor Day, 1949. Welcome to Simi Valley, Calif., to pick oranges! I was happy to be there. When the job was over I volunteered to join the U.S. Army. It was 1950, and the country was at war in Korea.

After basic training I was transferred to the U.S. Army Languages School at the Presidio in Monterey, Calif., teaching Russian to service men in the Army and Air Force. I applied for U.S. citizenship, and it was granted in 1953 four months after my honorable discharge from the Army.

After discharge and two years of college I went to work as a draftsman for Hughes Aircraft in its Lunar Surveyor division. I had a “confidential” clearance and proudly felt like an American. My group received Zero Defect pins and was the envy of our coworkers.

I liked the desert so I moved to Palm Desert. Later I found friends in Phoenix and moved there in 1972. I continued to work as a draftsman in the engineering department of the city of Phoenix. I received four citations for my suggestions on how to cut costs. I retired in April 1987 at the age of 62.