A number of people — from Martin Mull to Thelonius Monk — have been given as the source for the saying "Writing about music is like dancing about architecture."

This slogan is regarded as a Good Joke on music writers, trying to do an impossible and foolish task. You can read about all the possible sources for the quote here. Personally, I don't care who said it.

It seems clear that a talented choreographer could create quite a thoughtful and illustrative dance about, say, the Frank Lloyd Wright house known as Taliesin. Work that builds on other work happens all the time, and often enough it creates new work that's well worth the effort of making and experiencing.

Of course, it is better to listen to music than to read about it. The job of a person who writes about music is not to allow readers literally to hear music, but to offer up information that might make some area of the art a little more accessible and interesting, perhaps by placing it in a new context.

Following that thread, there's a wonderful collection from a few years ago, "The Great Jazz Interviews, A 75th Anniversary Anthology." It's based on pieces that ran in the venerable jazz magazine DownBeat, beginning with a 1935 interview with Louis Armstrong and a piece from the next year with Duke Ellington.

Jazz was likely the first popular music form to get serious critical attention. By the time commercial recordings became widely available in the 1920s, jazz was in full cry. Jazz originals like Armstrong and Ellington made brilliant music in commercial contexts and gave interviews to magazines such as DownBeat, just as actors and Broadway performers talked to Variety and other trades.

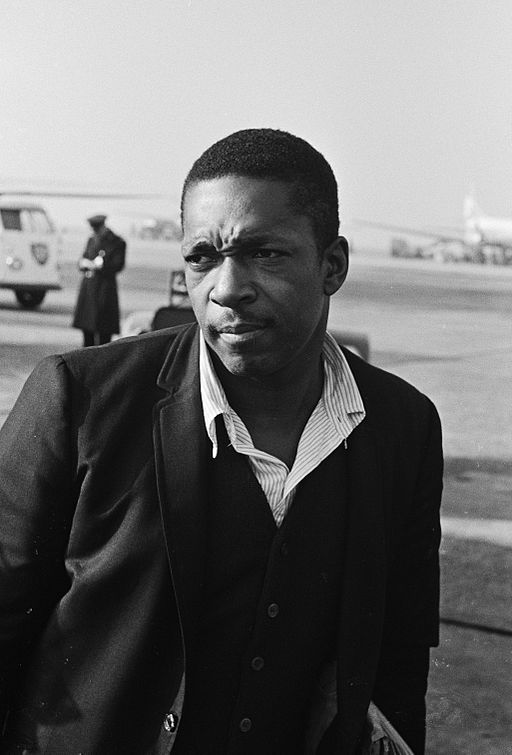

As they did in theater, critics in jazz came to have significant power over artists' careers. A case in point arises in the DownBeat book in a 1962 joint interview with the powerful jazz men John Coltrane and Eric Dolphy. They had experienced critical resistance to their long-form, harmonically extended improvisations. The mighty DownBeat itself had referred to their music as "anti-jazz."

Coltrane and Dolphy evidently cared about what critic John Tynan had said about their music when they agreed to an interview with Don DeMichael, also from DownBeat.

"The best thing a critic can do," Coltrane says in the interview, "is to thoroughly understand what he is writing about and then jump in. …

"Understanding is what is needed. That is all you can do. Get all the understanding for what you're speaking of that you can get. That way you have done your best."

Listeners have spent, do spend and will spend lifetimes listening to Coltrane and still strive for understanding. Coltrane's sweeping "My Favorite Things," like "Hamlet" or Picasso's "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon," will speak in different voices as we grow in understanding.

More recently I found in a new book, "Anyone Who Had a Heart," a trail of understanding that led me from one of the earliest classics of motion pictures through the Beatles and into the new century.

The book is an "as-told-to" biography of Burt Bacharach, the songwriter who collaborated with lyricist Hal David to create some of the most evolved popular music of the modern era.

A string of hits, notably for Dionne Warwick, included "Walk on By," "Anyone Who Had a Heart," "Do You Know the Way to San Jose?" and many others. Many were aching-heart songs with remarkably sophisticated chords, melodies and time signatures. They appeared during a period of American pop — the late '50s and early '60s — long derided as a musical wasteland thirsting for revival through the Beatles and other adventuresome acts.

Bacharach studied piano seriously and was strongly influenced by the 20th century classical music of experimentalists such as Schoenberg and Milhaud, as well as by pop titans such as Irving Berlin and George Gershwin.

One of Bacharach's longest associations, one that continued for years after he became a huge hit songwriter, was his role as pianist and conductor for the German actor and singer Marlene Dietrich.

"I can't love him any more than I love him right now," Dietrich said in 1964, introducing Bacharach to a London audience.

After that introduction, Dietrich, at 63, sings "Falling in Love Again," a hit from her classic film "The Blue Angel." Released in 1930, the unforgettable film tells the story of an aging professor, played by Emil Jannings, who falls hard for the nightclub singer Lola, played by Dietrich. It's a bleak tale that ends with the professor's character, having lost all his position and pride, making a tragic fool of himself at a theater's center stage, all for Lola, the most fatal of all femmes fatales.

As I read the Dietrich portions of Bacharach's book, I thought, my God, it all fits together. The harrowing devastation wrought by Lola, the difficult tonalities of Schoenberg, the cynical cabaret culture of prewar Germany, the classic pop of Berlin and Gershwin, all came out in the music of Bacharach, in the devastating loneliness voiced by Dionne Warwick, singing "If you see me walking down the street, and I start to cry, each time we meet — walk on by."

Bacharach, Dietrich and the Beatles all met in 1963, at the famous Royal Command Performance during which John Lennon urged the people in the cheap seats to clap and those in the boxes to rattle their jewelry. The song the Beatles performed that night: "Falling in Love Again," from the "Blue Angel." They first performed it amid the lurid nightlife scene in Hamburg, in Germany.

It's a tangled tale and perhaps the links are more intuitive than strict. But after making these connections, I hear the Beatles a little differently, after listening to them for nearly half a century. I think differently about the nature of pop music before the famous part of the 1960s. I believe that Emil Jannings' howl at the end of "The Blue Angel" reemerges in John Lennon's scream: "I'm lonely, wanna die."

All this occurred because a book about Burt Bacharach put some unexpected energy in my musical travels, along with a glimpse of the understanding that was so important to Coltrane. For now I'm walking a treasure-lined path, replete with music, dancing a little, about architecture.