I have been requested by our son, an American Studies PHD, to write down my story of making flight jacket “patches” for Air Corps crews during World War II, which he feels should be preserved. Painting “patches” was part of my work as a civilian employee at Herington Army Air Force Base at Delavan, Kansas in 1943-45. It is a long way back to those days and many details important at that time may have been forgotten. Here’s what I recall.

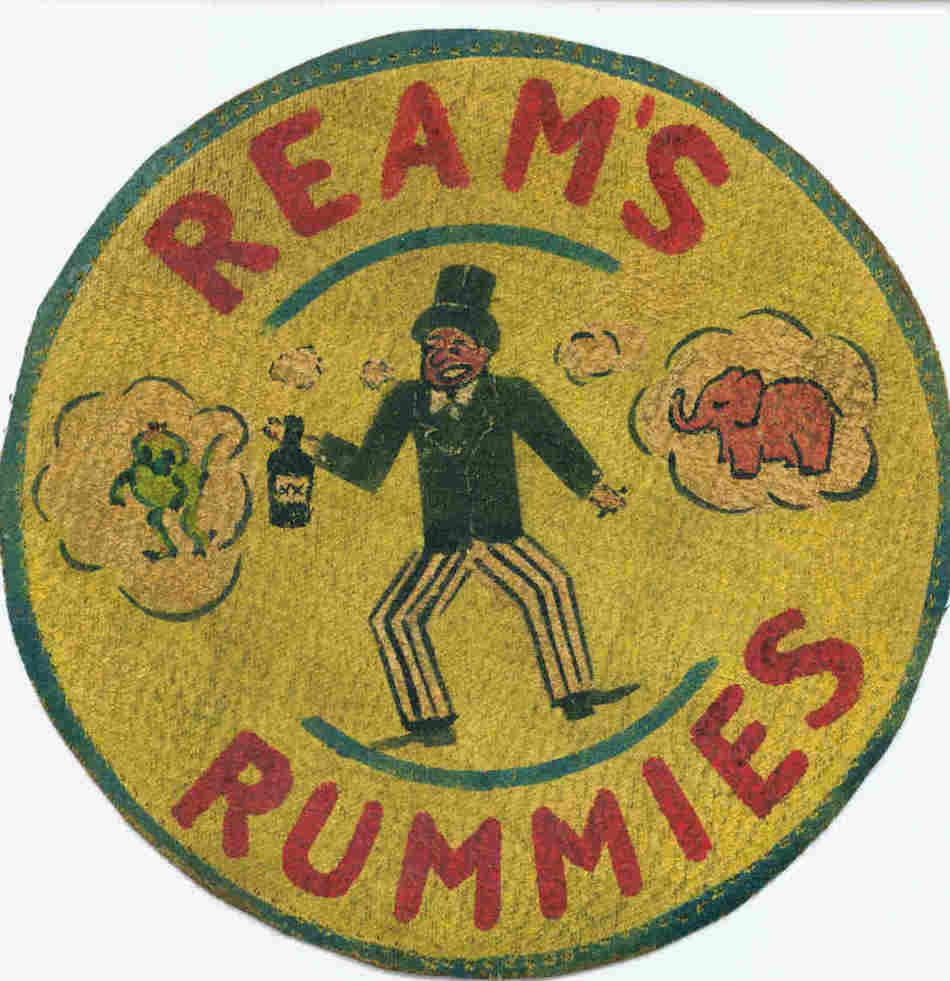

Patches were made from heavy cloth-like material prepared for painting, cut into circles, and hand painted with the name of the air crew and the design on their plane, which were then sewn on their flight jackets by another department.

There were four of us working in what was called “the Sign Shop,” Henry Litke, Virgil Carey, Dorothy Duddy and I. We had various degrees of art training and most of our work was making signs for the base and desk name plates for the Air Force brass, usually with gold leaf and Old English lettering. At that time almost all signs were individually painted except for the few which could be stenciled.

I had attended one semester of art classes at Drury College in Springfield, Missouri which was enough to get me hired, and it was a job I loved.

At first we were asked occasionally to work on planes right on the flight line. We remarked lines on the instrument panel of the B-29s, or we repainted pictures already painted on the planes but which were considered too improper — usually nude ladies to which we added a little clothing. There was always plenty of work for us.

As the war worsened and more and more Air Force crews moved through we began to get requests of a different kind. This was the beginning of the “Patches” painting for us. Our base was the next to the last stop before heading overseas on their mission and each crew wanted their own unique shoulder patches for their flight jackets before leaving the base. We wanted to oblige but the Air Corps said this was unnecessary and that we already had a full work load.

We in the shop experienced the disappointment of the crews first hand, but we also understood the reasoning of the Air Corps. We asked for permission to paint the patches for one insistent crew on our own time. Permission was granted.

It wasn’t long before we were working night and day turning out patches for crew after crew. Many of the designs were small versions of the designs and names already painted on the planes. Some crews wanted their own patch but had only a vague idea of what they wanted, so we created a design for them which took a lot more time.

We became pretty tired with all this extra work in addition to our regular hours and decided to charge a little, I think a dollar a patch, in part to discourage the men from requesting extra patches. Only much later did we consider that it would be nice to make a patch from each crew for our own keepsake. Some of the few that I kept are nicely displayed in an attachment made by my son Floyd.

Some of the Air Corps crews were at Herington much longer than others, depending on what their plane needed before departing for the job ahead. I wish that I could tell more about all these brave young men but there is one that I can tell about. He came home safely after 33 missions still wearing his patch. We were married for 67 years.

This article originally appeared in Roadrunner Extra!, the resident newsletter of Beatitudes Campus.